Documentation

Tribute page: to those who are no

longer with us in body, but who remain with us in

spirit and memory.

As I get older, the list of those whom I talk about in

the past tense increases: people whom I met in the course

of over 30 years of fieldwork in Georgia, who became my

friends, colleagues and mentors, but are no longer among

the living.

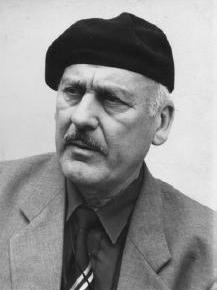

After a distinguished military career as an officer in

World War II and the following years, Mirian Khutsishvili

joined the Janashia Georgian National Museum in Tbilisi.

During his long career at the museum, Mirian participated

in ethnographic expeditions throughout the Caucasus, and

pioneered the use of movie cameras in the field. His

photographic and film archives provide invaluable

documentation of the highland regions of Georgia and the

North Caucasus from the early 1960s to the present day.

But even more than for his work as a visual

anthropologist, Mirian will be remembered by all who knew

him for his wisdom, warmth, enthusiasm and humor, his

insatiable love for the mountains and the people who lived

there. I was privileged to have had the opportunity to

accompany Mirian on several fieldtrips in the past 15

years. Although older than my father, Mirian easily

outpaced my friends and me on the narrow mountains trails

of Pshavi and Khevsureti. Every person met along the way

was greeted by Mirian. If he did not know the individual

personally, he invariably knew his father or grandfather!

No professor taught me as much about ethnology as did

Mirian, as I observed how easily and wholeheartedly he

interacted with local people everywhere we went, and came

to appreciate his immensely rich treasure-trove of local

knowledge. Anthropologists will long remember Mirian

Khutsishvili's contributions to the ethnology of Georgia

and the Caucasus, but the most eloquent and heartfelt

testimonies to Mirian as a man will be heard in Tusheti,

Pshavi, Ingushetia, Gori, Chailuri and many, many other

places.

LINKS

The Georgian National Museum's Visual Anthropology Collection.

Documentary films "Pshavi" and "Mtiulet-Gudamaq'ari" (Ilia University Visual Anthropology Laboratory)

Konstantine (Kote) Choloqashvili კოტე ჩოლოყაშვილი

(1922-2013)

Konstantine (Kote)

Choloqashvili was born into one of Georgia’s most

illustrious princely families in 1922, a year after the

Red Army invaded his homeland. I was fortunate to have

gotten to know Kote and his wife Ketevan through their

daughter Rusudan, a colleague and close friend of mine.

Sharing a meal at the Choloqashvili’s table, with Kote

presiding, was an extraordinary, unforgettable

experience: on the one hand, a display of the art of the

tamada at the highest level — eloquence, humor,

deep knowledge of Georgian tradition and history, — but

at the same time, a warm, friendly family dinner. Kote

would sometimes talk about the tragic fate of his family

under the new Soviet regime, but while telling their

story Kote never showed bitterness, anger or the desire

for revenge. I will leave it to others to tell the

history of his ancestors, or discuss his career as an

ethnologist at the Georgian National Museum. I will

remember Batoni Kote as more than a nobleman by birth;

he was a noble man by character and example as well

Wikipedia

profile of Kote (in Georgian)

Obituary

(in Georgian)

Philipe (Pilo) Baghiauri ფილიპე ბაღიაური (1933-2019)

Until he passed away in

early 2019, Philipe (Pilo) Baghiauri was the chief

khevisberi of the shrine of St George in Gogolaurta

Commune, Pshavi. Pilo came from a long line of shrine

priests, including his father and predecessor Betsina

Baghiauri. I first met him in 1997, and over the years

he became my principal source on the vernacular religion

of northeastern Georgian highlands. Pilo was one of the

last khevisberis who received their call to service in

Soviet times, when the practice of traditional religion

was still discouraged by the authorities, and the

necessary knowledge was transmitted orally, by

observation and memorization. But for all of his immense

knowledge of ritual texts, practices and norms, Pilo was

refreshingly down-to-earth, unassuming and a pleasure to

be around. Along with a handful of other old-time

khevisberis (Ioseb Kochlishvili, to name one), Pilo

possessed what Georgian refer to as madli —

grace, virtue, or perhaps charisma in something like its

older sense. The vocation of khevisberi was never freely

chosen — Pilo and others of his generation described

their struggles against the will of their divine

patrons, and the heavy cost they paid for their

stubbornness — and there was no material recompense for

the burdensome responsibilities that they assumed once

in office. By North American standards, Pilo lived in

poverty, and yet he considered himself the richest man

alive. And I consider myself all the richer for having

known him.

Interview with Pilo

Baghiauri

Obituary

(Mtis Ambebi)

Video-blog

(Georgian)

Mirian Khutsishvili, Pilo Baghiauri & his mother,

2001, Pshavi

Felix Glonti ფელიქს ღლონტი

(1927-2012)

Dernière modification 2020